The Equity Case for Competency-Based Hiring

In January 2015, Minneapolis College launched a pilot program that used competencies and skills over credentials as the measure for hiring staff positions. The pilot was implemented to remove hiring barriers inherent in candidate evaluations based primarily on education and work experience. The program also allowed the college to identify talent based on skillset and qualities to ensure the best fit for the position.

The college found that the move to competency-based hiring not only improved the quality of the hire, but also led to significant increases in hiring diverse candidates. This resulted in an impressive increase in employee retention, which, in turn, resulted in Minneapolis College being named a workforce diversity leader in the Minnesota state system.

Because faculty job qualifications are governed by accrediting bodies, the pilot program explored a competency-based model with staff positions. However, components of this model can be expanded to faculty searches as well, and the college has begun taking steps toward that.

Lightbulb Moment

Minneapolis College is an urban, diverse, comprehensive two-year college in the heart of the city. The college is one of 37 colleges and universities in the Minnesota State system and has 10,000 students, 55 percent of which are students of color.

In the fall of 2014, the Minneapolis College Human Resources Division was in transition. The division was under new leadership and several new staff members had joined the team. One of the new HR specialists was working with a supervisor to fill a position for a college recruiter in our admissions department.

The newly staffed HR division had inherited a long-standing hiring model, using a process that required search committee members to rank candidates based on a number of factors listed in the vacancy posting. These factors included both minimum and preferred qualifications, most often focusing on education and job experience. The posting for the admissions recruiter, for example, required candidates to have a bachelor’s degree (a master’s degree was preferred) as well as three years of experience as a recruiter. This was the typical combination of qualifications for entry-level professional positions at the college.

The process then required search committees to rank candidates based on the minimum and preferred qualifications. More points were awarded to candidates with master’s degrees and more years of experience in similar fields. While this approach seemed to provide a neutral method for evaluating candidates based on qualifications, it soon became apparent that the process, with its reliance on education and experience to the exclusion of other important qualities, was deeply flawed and created barriers to hiring talented, diverse candidates.

Internal Case Study

Using the standard ranking system, the search process for the admissions recruiter position yielded eight candidates for interviews. These candidates were clearly competent, but a serious problem existed that was not apparent solely by looking at the list of the top eight candidates. Instead, the issue was about who did not make the list.

For example, one candidate who did not make the interview list was an alumnus of Minneapolis College, who, after completing his associate degree, transferred to one of our partner state universities where he completed his bachelor’s degree. This candidate had impressive volunteer experience serving underprivileged youth through a local nonprofit agency. At the time of his application, he was working in a student-serving capacity with a local K-12 school district in our target market for admissions recruiting. However, this candidate did not earn enough points to be selected for an interview because he did not have a master’s degree. And while he had impressive volunteer experience and K-12 experience, he never held a position as a recruiter. And at that time, volunteer experience was not given the same value of paid work experience, even if the experience was directly relevant to the position.

Another candidate who did not make the interview list held a position at a similar-sized and similarly diverse two-year college in a metropolitan area. He held a bachelor’s degree and his position was student-serving, but it did not involve recruiting. Because he lacked a master’s degree and recruiting experience, he was not awarded points that other candidates with master’s degrees and recruiting experience earned, and thus, did not make the interview list. Additionally, both candidates were people of color.

In contrast, the candidate with the highest number of points was a woman with a master’s degree who had several years of experience as a college admissions recruiter at a smaller, less diverse college. The second highest ranking candidate held a master’s degree and had five years of experience as an athletics recruiter at university in a rural area. This candidate had no experience in a two-year college and lacked experience working in an urban setting.

Both candidates earned points for their master’s degrees, and both were determined to have the requisite recruiter experience that earned them additional points. Both candidates were White. In fact, all eight of the top candidates were White.

These results demonstrated the serious flaws in a system that placed too much value on the level of education attained and previous similar work experience. It was very clear that the system was broken, and Minneapolis College was determined to find a different approach.

Research

The first step to addressing this issue was digging into research. It was important to understand issues related to labor trends, education attainment and alternative approaches to hiring. Ultimately, there were key themes of research that were critical to understanding the real problem with the traditional hiring model being used.

The first theme that emerged from the research was the issue of underemployment:

- At the time, data showed that 49 percent of the state of Minnesota’s working adults were underemployed. That is, working at jobs for which they are overqualified.

- 282,648 Minnesotans with bachelor’s degrees worked at jobs in 2012 that required only a high school diploma.

- Another 60,580 four-year college graduates worked at jobs for which not even high school completion was required.

- At the time of the initial research phase of this project, three out of five Minnesotans with bachelor’s degrees held jobs that did not require one.

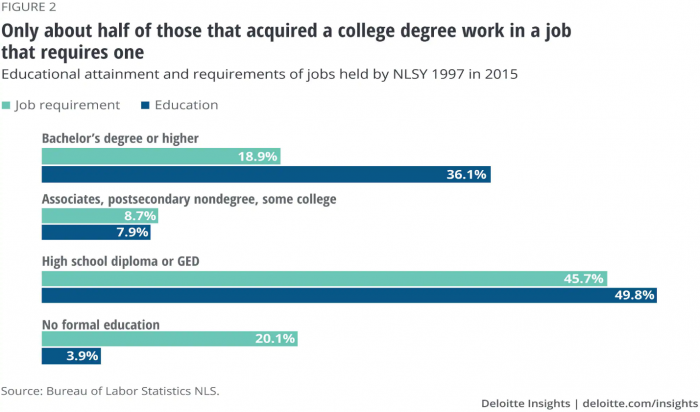

National data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2015 was similar. It showed that only about half of those who acquired a bachelor’s degree worked in a job that required one.

Minneapolis College, like many employers, believed that hiring candidates with bachelor’s degrees, and better yet, master’s degrees, resulted in better, more talented employees. But there was simply no evidence to support this belief. Instead, the research led us to believe the opposite — that hiring overqualified employees is detrimental to organizations because it leads to dissatisfied workers and high turnover.

A second theme that emerged was with the issue of job demand and job requirements. While labor data showed a trend of underemployment for candidates with bachelor’s degrees, some economists, like those who conducted a study from Georgetown University Center on education and the workforce, suggested that America’s postsecondary education system would not be able to keep up with the demand for jobs requiring college degrees.

In doing a deeper dive into this issue of job demand, Minneapolis College learned what might appear obvious. Many labor and education research organizations regularly issue labor trend reports that include lists of jobs that require college degrees.

The important question then was: who determines which jobs require college degrees as listed in these reports? The answer is surprisingly simple. These research organizations gather data from job vacancy postings and employer surveys. So, to answer the question, employers determine which jobs require college degrees. In most cases, employers make these determinations without any evidence that the degree required is necessary to do the job. The requirements are based merely on beliefs about what makes a good candidate and the belief that if candidates have earned a particular degree, they will have the requisite competencies and skills required for the work. And while a college degree indeed develops skills, they don’t necessarily correlate to job success.

There are certainly jobs that require college degrees. Positions such as teachers, lawyers and healthcare workers require specific degrees and licenses that are issued by independent governing bodies. However, when a legal requirement for a specific education credential is absent, it’s completely up to the employer to determine the education requirements for the job. There are simply no rules that prevent an employer from hiring a marketing professional, an information technology specialist, an accounting technician, an HR specialist, an admissions recruiter or any other staff member who does not have a bachelor’s degree.

A hiring model that gives preference to degree-completers, without any evidence that the degree is required for the job, is a perfect example of structural bias.

Equity Issues

The research also unearthed compelling information about how the traditional education and experience-based hiring model for non-licensed staff members created a barrier to inclusive hiring. This equity issue is rooted in the educational attainment gap that exists in higher ed today.

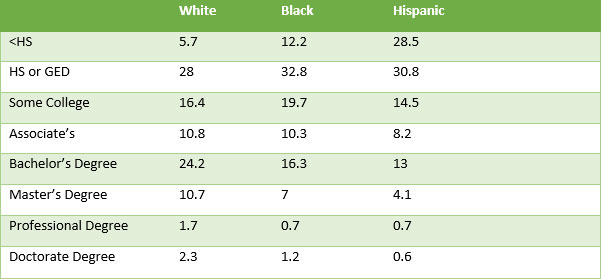

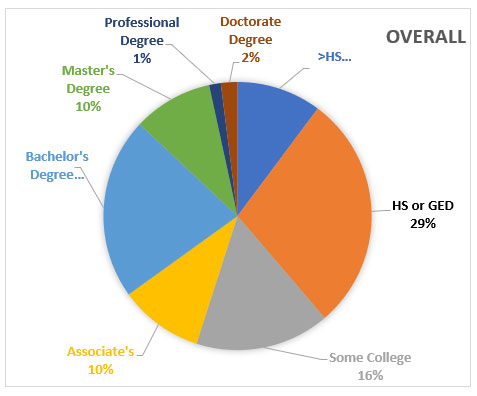

Source: Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics 2018

Why is education attainment important for hiring considerations? Because a staffing model that bases hires predominantly on education attainment merely transfers the attainment gap from the higher education system to the workforce. In other words, demanding bachelor’s and master’s degrees, where those degrees are not actually needed to perform job functions, creates a barrier to employment for individuals who, except for arbitrary minimum qualifications, have the competencies to perform the job.

As the diagram indicates, the percentage of Black individuals who attain bachelor’s degrees is lower than the percentage of White and Asian degree completers. This attainment gap grows at each level of education with a greater gap at the master’s degree level and an even greater gap at the doctoral level. The data demonstrate that when employers set an arbitrary requirement for a bachelor’s degree or a master’s degree, it restricts access to a smaller percentage of eligible Black candidates.

Higher education systems understand that the attainment gap is the consequence of longstanding structural and systemic bias. Structural bias can be defined as a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate underrepresented group inequity. A hiring model that gives preference to degree-completers, without any evidence that the degree is required for the job, is a perfect example of structural bias.

Minneapolis College chose to dismantle the structure.

The Transition to a Competency-Based Model

Minneapolis College did not invent competency-based hiring, but it became clear to the HR team that a hiring model that allowed candidates to be evaluated based on their skills, abilities, qualities and passion for the mission of the college made sense.

What is competency-based hiring? There are various definitions of competency-based hiring in HR literature, some with very complex models of attempting to identify the precise competencies required for every job type. At Minneapolis College, the HR team started with a simpler definition, similar to the one by Barbara Bowes, president of Legacy Bowes Recruiting Group, and an ardent believer in competency-based hiring. She describes it as “simply the ability to do something successfully or efficiently.”

For each vacancy at the college, HR created a list of skills, abilities, knowledge and qualities that a candidate needs to be successful. Doing this required an analysis of the position, consultation with the hiring manager and an inquiry into what traits and skills have made other candidates in similar jobs successful.

Rather than implementing a comprehensive model that required rewriting every position description, the college decided to focus on rethinking job requirements as positions became vacant. This seemed to be a more manageable approach to launching the pilot.

After having failed the admissions recruiter search, the college implemented the first competency-based vacancy notice to repost the position, and established the following minimum qualifications:

- Associate’s or bachelor’s degree

- Ability to build and maintain relationships with school district and community organizations as sources of new student enrollment

- Must understand the diverse communities of Minneapolis and demonstrate the ability to develop relationships with these communities to promote Minneapolis College as an educator of choice

- Must have communication skills to promote Minneapolis College to prospective students and parents, explain the benefits of higher education and guide students in the admissions and financial aid processes

- Ability to plan outreach events

Preferred Qualifications:

- Knowledge of two-year college academic programs

- Experience with recruitment tracking software or similar software or ability to learn

After careful consideration of this position, it made sense that an employee whose primary duties are selling a college degree should have one. However, the college determined that an associate degree was the appropriate minimum qualification. The inclusion of bachelor’s degree was a compromise with a hiring manager who was reluctant to give up on the idea of candidates with bachelor’s degrees. Eventually, however, the college moved away from this type of posting for education requirements.

Challenges

This new model posed two significant problems. The first problem was getting hiring managers to buy in.

Prior to rolling out the pilot, HR met with supervisors for consultation. Many supervisors were reluctant and held firm to their beliefs that their staff members should have bachelor’s degrees and better yet, master’s degrees.

HR conducted an exercise with managers that had them think about a highly successful staff member in their units. Then, supervisors were asked to describe what made those employees rock stars. Managers said things like, “He knows how to develop relationships with students,” “He has outstanding communication skills,” “She is highly detail-oriented and has excellent analytical skills,” “She cares about people,” “She has amazing organization skills,” and “He is a confident presenter.”

Not a single manager said anything like, “His college degree makes him amazing,” or “I really value his bachelor’s degree.”

It’s true that some employees may have developed those skillsets in college. But it’s also true that the college could miss out on other talented candidates who possessed the same skillset but didn’t have a college degree.

Another challenge related to supervisor buy-in was the concept of higher education institutions needing to require the very thing they were in the business of: college degrees.

Many managers and colleagues questioned whether the college was devaluing a college education by taking the position that a degree was not necessary. This was a valid concern. From an HR lens, the college was struggling with a polarity and needed to hire people who were dedicated, talented and served and represented our student body. Furthermore, the college needed to stand behind a college education as a critical path to meaningful employment and personal economic success.

The HR team addresses this polarity by continuing to emphasize our commitment to staff development and the tuition waiver that allows employees in the Minnesota State system to pursue a college education.

Dedicated, talented employees are critical to student success. The more success we have among our minority student body, the more students of color will move the dial on education equity gaps. This is not a chicken or egg dilemma. The Minneapolis College HR team believes that hiring the right people is more important in advancing equity and helping to close the education attainment gap than the philosophical position that higher education institutions must require employees to have college degrees.

The second challenge to the model was the amount of time it required of HR. The existing hiring model was efficient for HR staff. HR specialists could easily create queries in the applicant tracking programs to quickly weed out anyone who didn’t meet the education and work experience requirements. Holistically evaluating every candidate for the more intangible competencies and qualities was much more difficult. The truth is, it is a lot of work. But the HR team thinks it is worth the extra time because the model eliminates barriers, dismantles a structurally biased hiring model and reduces turnover.

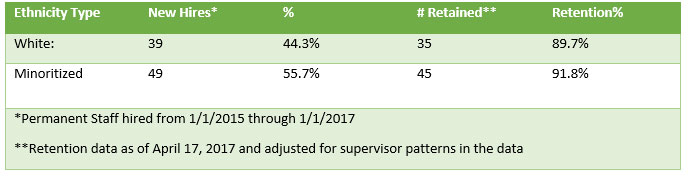

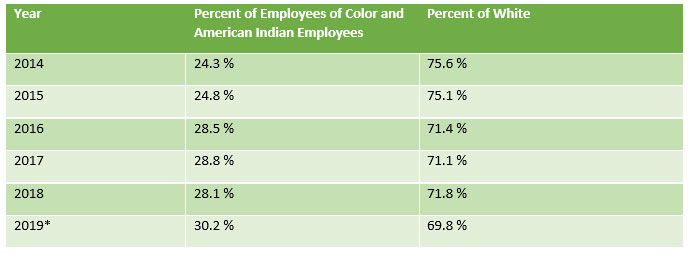

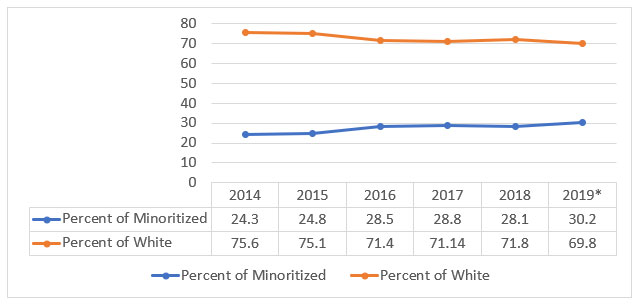

Minneapolis College competency-based hiring results (data analysis after the first two years):

Increase in overall workforce diversity 2014-2019:

As the data show, the college saw a statistically significant increase in the diversity of our employees after 2015. That trend continued through 2019, making Minneapolis College a leader in overall workforce diversity in the Minnesota state system.

Expanding the Model to Faculty Hires

It is possible to expand this model to faculty hires. Minneapolis College is doing just that. While faculty qualifications are governed by accrediting bodies, higher education institutions often include preferred job requirements for faculty that far exceed those qualifications. Like with staff positions, faculty job postings place significant emphasis on the level of degree requirements. At two-year institutions, doctorate degrees are generally not required for teaching, yet many community colleges include them in job requirements. And while these advanced degrees are important and bring credibility to institutions, including requirements that go far beyond what is actually required to the exclusion of other factors is problematic.

As Minneapolis College expands the concept of a competency model for faculty, it will look to balance the desire for a highly educated faculty with the need for other important competencies and qualities for teaching in a highly diverse two-year college. Stay tuned, as the college will report its findings from this next phase of its commitment to competency-based hiring.

COVID-19 update from the author: Like most everyone in our industry, it’s difficult to pause long enough to think about how COVID-19 has changed our work. The better question is how hasn’t it? At Minneapolis College we have completely transformed the way we work, moving 95 percent of our workforce to working from home and all of our course offerings to online. Our commitment to diverse hiring has not changed. Our hiring, however, has. In anticipation of the severe financial implications for our college, our system and our state, we have implemented a hiring freeze, following the example set by our state government and higher education system leaders. When this hiring freeze is lifted, our college will resume its serious efforts to attract, hire and retain diverse candidates. And it is my belief that the strategies I’ve detailed above will be even more important to ensure a working and learning environment committed to the principles of equity and inclusion in all aspects.

About the author: Dianna Cusick, J.D. is vice president of human resources and workforce equity at Minneapolis College.